Do you find herbal medicine too costly to access, even when you make your own preparations? The other day I had a discussion with some of my fellow herby friends about how expensive medicine-making can be. All of the equipment adds up – secateurs, handsaws, baskets, and knives for harvesting; the jars, funnels, strainers, cheesecloth, drying racks, and food processor for processing plant material; the high proof alcohol, vinegar, isopropanol, honey, oil, or glycerine to extract the plants into. God forbid you get into anything fancier (like making lotion bars, a new and pleasurable yet incredibly indulgent hobby of mine). This, of course, also excludes the costs associated with any herb growing or purchasing you may do, the time you devote to these activities, and a myriad of other little bits and bobs.

It doesn’t sit right with me that herbal medicine, the People’s Medicine, which humans have been practicing since the Paleolithic Age, could be cost-prohibitive. I have found such freedom in identifying and harvesting plants as a way to grow closer to the land I call home and have discovered the act of supporting my body and spirit with plant medicine to be incredibly empowering. It is counterintuitive that such a natural, instinctive form of medicine is accompanied by the barrier of cost.

Really, this barrier is novel. Before the rise of the pharmaceutical industry in the 20th century, everyone practiced herbal medicine (and most people in the world still do). But mothers weren’t rushing off to get organic, non-GMO, sustainably derived, pure vegetable glycerine to make a glycerite with every time their child developed a cough; rather, they often took advantage of the most effective and readily available menstruum there is – water. Water is the universal solvent – unlike other substances, it efficiently extracts almost all plant constituents, from vitamins and minerals to mucilage, tannins, and volatile oils. Making tea is the oldest trick in the book.

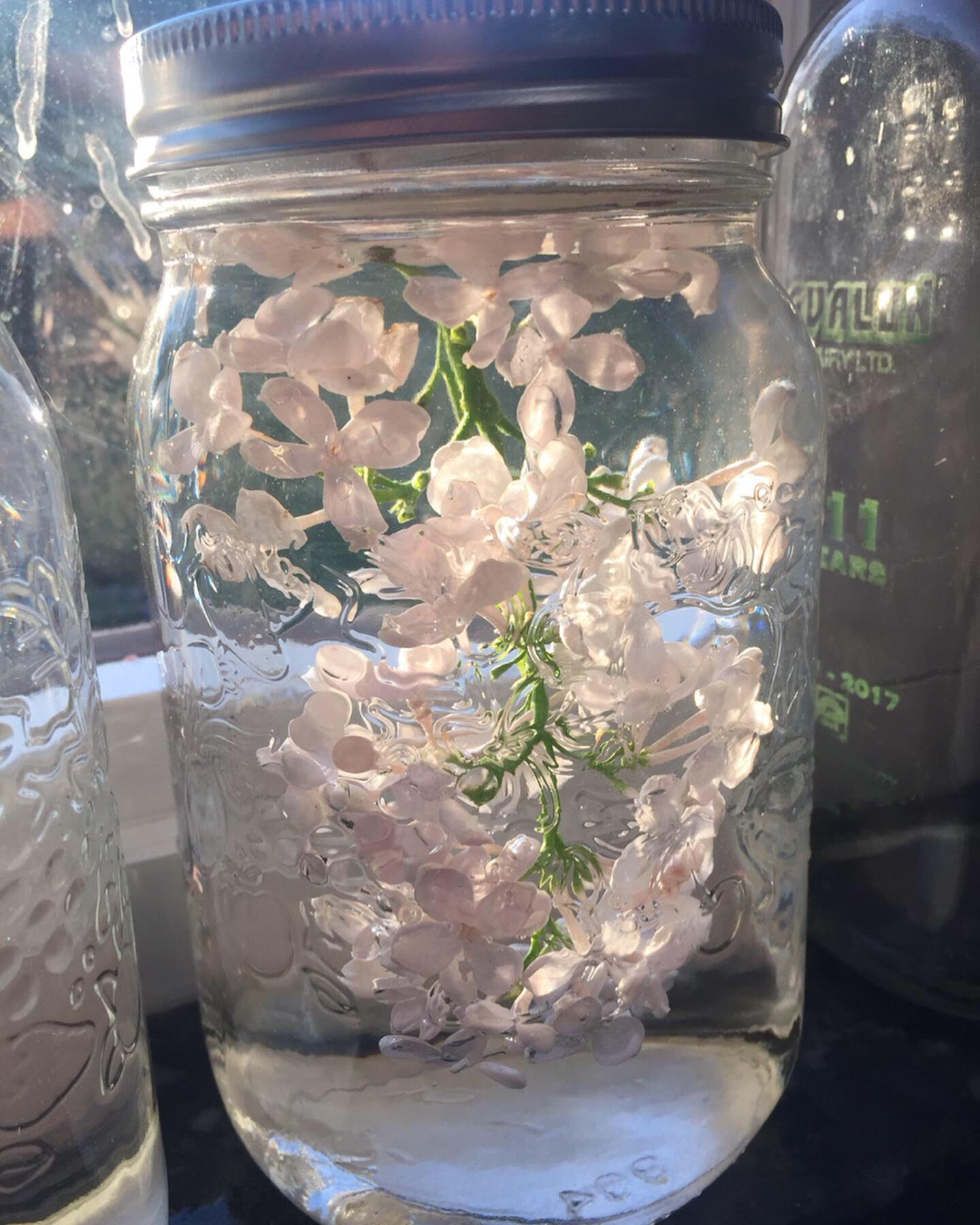

These water extractions are referred to as herbal infusions. Cold infusions are made by pouring room temperature water over the plant and letting it steep for a few hours minimum. They are best suited for herbs high in volatile oils (i.e. the ones that smell strongly) such as lemon balm, peppermint, or Western red cedar. Hot infusions are what we commonly refer to as tea, wherein hot water is poured over the plant and steeped for around 10-30 minutes or more. Hot infusions can be made for most plants, particularly when using leaves and flowers. When steeping, it is beneficial to put a lid or covering on the vessel to prevent volatile oils from escaping. Decoctions, the third type of infusion, are made by pouring cold water over the plant material and then slowly heating it up to a boil before turning it down to simmer for 10-30 minutes. This method is suitable for tough plant parts such as roots, berries, and bark.

Water tends to extract more medicinal constituents from dried plants over fresh, so dried plants can be preferable and (and more accessible year-round). To improve potency, it helps to chop the plant up as finely as you can – the greater surface area of the plant, the more contact it has with water. You can play around with the ratio of herb to water, but medicinal-strength infusions usually use a ratio of 1:20 for dried plants (that is, 1 g of dried herb to 20 mL water) or 1:10 fresh (1 g to 10 mL, which is at least 4 times stronger than your average beverage tea). If you don’t have a scale to weigh out your herb, you can just estimate the amount you need, keeping in mind that the fluffier the herb, the more you’ll probably need to add. These ratios can also be taken with a grain of salt – you may want to further dilute bitter, spicy, or otherwise unpalatable herbs.

You don’t necessarily have to drink your infusions – they can also be used in baths, washes, or compresses. For instance, along with Epsom salts I like to dress up my weekly bath with dried calendula, lavender, chamomile, and comfrey leaf (all contained within a cotton bag) to add anti-inflammatory, calming, and skin-nourishing properties. Decoctions of Western red cedar and yarrow both make wonderful wound washes, and a compress of chamomile tea can be incredibly soothing for sore eyes. Steaming with herb-infused water can also be a wonderful way to open up the respiratory tract and sinuses, and as an added bonus it is also great for your skin! For facial steaming, potent aromatic herbs are especially useful, including oregano, thyme, rosemary, basil, and peppermint, but you can also incorporate anti-microbial/ant-inflammatory plants (e.g. yarrow, usnea, sagewort, Western red cedar) and expectorants/lung herbs (e.g. mullein, hyssop, gumweed, plantain). You can also try the traditional practice of pelvic steaming to help with circulation, fibroids, cramps, and other hormonal issues, though you should do more research to make sure you know what you’re doing before you try this one.

If you are having trouble figuring out how to incorporate more plants into your life, infusions are such an accessible way to experience plant medicine. Chances are you’ve already experienced the joy of herbal infusions with a mug of peppermint tea after dinner, chamomile tea before bed, or by soaking in an oatmeal bath to help with a bout of chicken pox. A fun experiment to try is to make a hot infusion, cold infusion, and decoction with the same plant to see how these preparations differ. Alternately, toss a few mint leaves or rosemary sprigs in your water bottle then sip it throughout the day. Clear out your pipes this cold and flu season with a warming herbal steam. Up your self-care game by adding rose petals to your bath. Spray down your counters with an anti-microbial decoction. Get rid of your maskne with a hot compress or steam. Plant medicine is for everyone – we co-evolved with plants, and creating relationships with them is not exclusive to those who can afford fancy equipment. Connect with your ancestral roots and the land as you enjoy the simple pleasure of herbal infusions this winter.