I have quieted down on here in the past few weeks to make space for the important dialogue going on concerning institutional racism and the BLM movement. I’ve been taking this time to reflect on my privilege, check my biases, and come up with ways in which I will actively be anti-racist and a better ally moving forward.

Part of my intention for Farm and Forage was to share ways in which the industrial food system is inherently unjust. Racism is inherent within agriculture. Land stolen from the Indigenous people of Turtle Island was cultivated by Black slaves who, after the Civil War, were promised 40 acres and a mule. This promise was reneged by President Johnson – land that would have been worth $6.4 trillion today was never passed over to the ones who had worked it for generations. At the beginning of the 20th century, Black people owned 14% of farms. This land was violently stolen by whites. In the US, only 2% of farmers are black as of 2017, and less than 2% are Indigenous. Slavery lives on with the exploitation of prisoners and undocumented immigrants working the fields and harvesting our food.

Having access to fresh food is a privilege. Living in a food swamp with no grocery stores or markets leads to overconsumption of disease-causing fast and pre-packaged food, thereby enforcing oppression as marginal populations carry the burden of chronic disease. Food insecurity also leads to overconsumption of this lab-created quasi-food, designed to be addictive despite its dearth of nutrients, and specifically marketed to BIPOC and the poor. The exploitation from Big Food corporations further entrenches inequality – the discriminatory targeting of these populations is unethical, as is the influence that Big Food has on public policy.

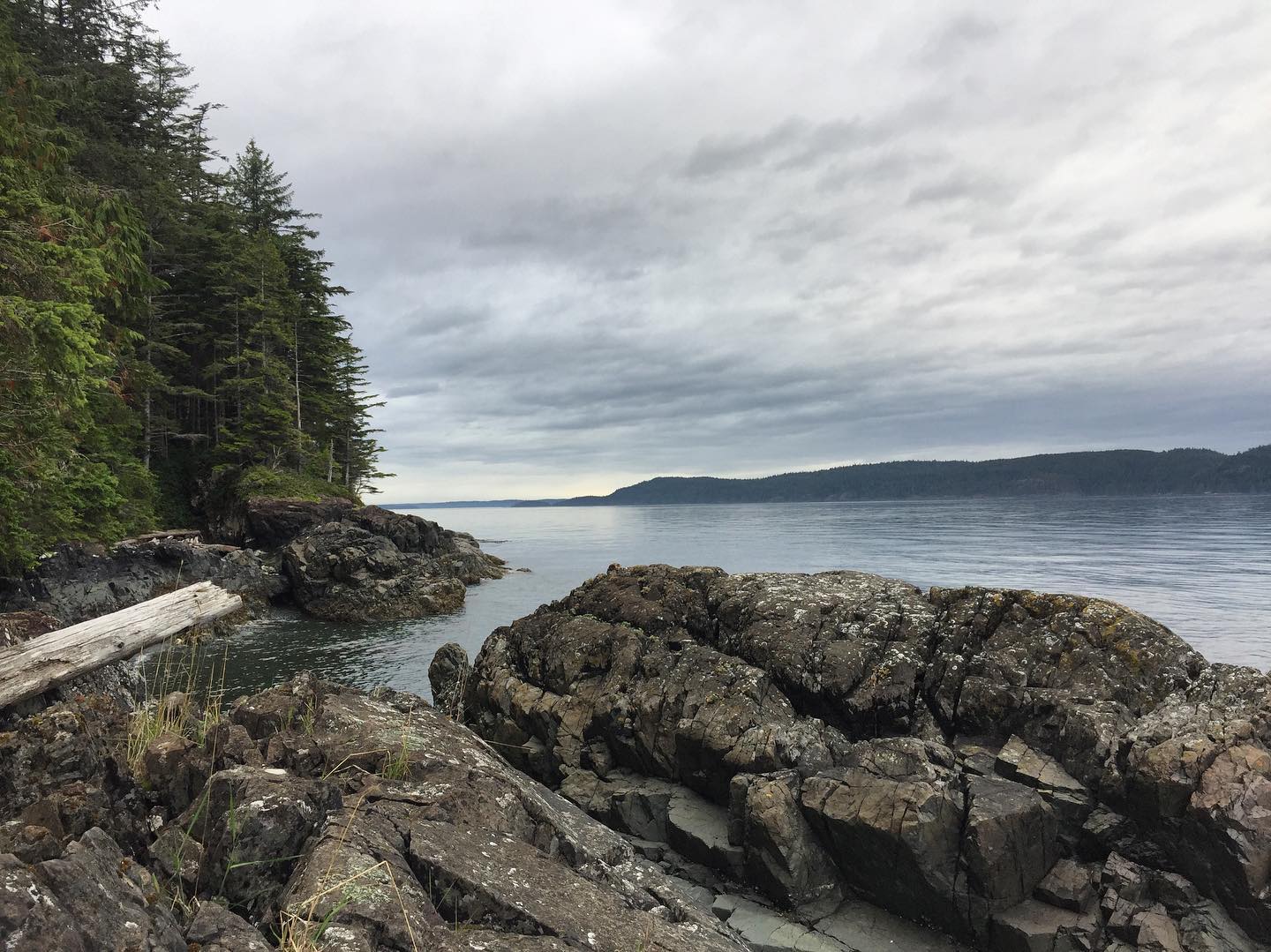

Similarly, the ability to access natural areas is a privilege. Being able to go out onto the land and spend time with plants is a practice not available to everyone. Learning about plant medicine can also be neocolonial – claiming Indigenous knowledge as one’s own without paying proper respect to the traditional stewards of the land who have kept this knowledge for tens of thousands of years, through generational trauma, forced assimilation, and cultural genocide, is cultural appropriation. Similarly, valuing plant medicine in a reductionist way for purely physiological effects (i.e. Ignoring the spiritual aspects) is a Western ideology, and applying it to herbal medicine is neocolonial.

The truth is that there is so much to be discussed and dismantled within this realm. A million blog posts would never be even remotely adequate to delve into these truths. I vow to become a better, more active ally and project BIPOC voices.